Inside the Great Mind of Pete Sampras

October 2000, Issue 48

Pete Sampras doesn't often open up to journalists. The player who, with his record-breaking 13th Grand Slam singles title and record-equalling seventh Wimbledon crown is now more than ever rated by experts as the greatest tennis player of all time, guards his privacy with a passion. But in this interview he reveals that he was always a solitary child and teenager who wasn't into dating girls and even now would never "live loosely."

He

speaks of his original loathing of grass tennis courts and the stress of

finishing 1998 as No. 1 in the world for the sixth year running. Also, he

owns up for the first time about a low-iron blood condition which leaves

him debilitated and lethargic in very hot weather, and his feelings about

the imprisonment of his first coach, Pete Fischer, for child abuse.

He

speaks of his original loathing of grass tennis courts and the stress of

finishing 1998 as No. 1 in the world for the sixth year running. Also, he

owns up for the first time about a low-iron blood condition which leaves

him debilitated and lethargic in very hot weather, and his feelings about

the imprisonment of his first coach, Pete Fischer, for child abuse.

Sampras, who announced his engagement to actress Bridgette Wilson just before Wimbledon, currently lives in a spacious hillside ranch-style house in Benedict Canyon, an exclusive suburb of Los Angeles. Since moving back to the area from Florida he has become much closer to his parents, who joined him for the first time ever at Wimbledon this year. But they were once so poor that his father had to do two jobs and his mother had to sleep on a cement floor.

Pete on Fame and Fortune

Q. If you look around this place and then think back to yourself as a happy-go-lucky, grinning 15-year-old, did you ever think you'd wind up having all this?

PS: Yeah, I assumed I would be successful, because everybody predicted it for me, although it would have been hard to forecast this degree of success. Sometimes, if I happen to glance at the trophies on the bookshelf, I'm a bit overwhelmed. But this level of comfort was never a priority, because I don't need a lot to be happy. I've always led a simple life with few extravagances. The money in tennis never drove me. When I turned pro, I often shared a room on the road with my brother, Gus, to keep expenses down.

Now I can have all the luxuries and conveniences, like a jet and nice cars. I know my family will always be secure. That means a lot to me. What is a little strange is that when I first turned pro, I wasn't sure I wanted to experience this level of success in tennis. But a few things happened at the start of my career to make me realise that I did want it.

Q. Did fame really hit you that hard?

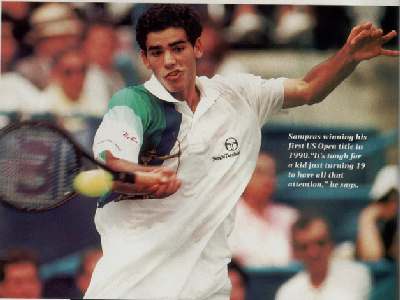

PS: Oh yeah. When I won the [US] Open in '90, I wasn't ready. Not as a person, and not as a tennis player, I just happened to have two great weeks. That's the only way to explain it. Otherwise, I was a really green, insecure kid.

The morning after I won, I did all these talk shows. And they made me feel intensely uncomfortable. It's tough for a kid just turning 19 to have all that attention. I was a shy, immature kid and that came across. Suddenly, everybody always expected me to be in a good mood. But all I really wanted, like most 19-year-olds was to find a comfort zone as a person, to fit in. And fame wasn't my idea of it. I got overwhelmed trying to figure out what people wanted from me. I also saw that what I'd done would affect the rest of my life, and that was scary. On top of that, I knew my game couldn't support what I'd created. After winning that US Open, I began to feel like a marked man on the court, and I really wasn't a good enough player yet to ward it off. I just had a two-week fairy tale, and then this price to pay - the responsibility of backing it up.

It took me a couple of years, pretty much until I won the US Open for the second time in 1993, to figure it out mentally, and to develop a good enough game to defend my position.

Here I am complaining about winning the US Open. But if I had to do it all over again, I would rather have won it later.

Q. After you lost in the US Open quarterfinals in 1991, you held a memorable press conference in which you said you felt relieved that the pressure was off. Consequently, a number of players, including Jim Courier and Jimmy Connors, hauled you over the coals for it. Did you mean what you said, or did it just come out wrong?

PS. I remember that episode well. It was one of the two or three real media low points for me. But you know, I just went into that interview room and said what I felt.

It was what I was feeling at that time although it came out sounding like I was happy to lose. And it reflected that while I had a lot of talent for the game, I had no real idea back then of what it took mentally to be a consistent, Grand Slam-level winner.

Pete on Champion Quality

Q. Do you think that champions are born or made?

In my case, I'd probably have to say born. At the most basic level, this game comes easily to me. I was born with the right genes, I guess. But, despite being given that talent, I did have to make myself a certain way, mentally. And in that sense, I'm made. It's a little deceptive, maybe because I'm not one to go to sports psychologist to have complicated charts breaking down my game, or to leave no stone unturned in looking for an advantage. But I never would underestimate the mental aspects of playing this game. I just operate a little more naturally.

Q. You've often

expressed an aversion to over-analysing things. Is that really your temperament,

or is it a means of self-protection against a prying world?

Q. You've often

expressed an aversion to over-analysing things. Is that really your temperament,

or is it a means of self-protection against a prying world?

It's me, more than the situation I'm in. It's the way I look at my life, and my tennis: Keep things as simple as possible, and shy away from analyzing every little thing. Don't over complicate things.

I know people sometimes have trouble understanding my tennis, and they try to figure out why I'm successful. But for me, it's always been very simple and natural. The game is something I take for granted. When I'm playing well...it's easy. And that's how I've always approached it. I'm the kind of person whose first reaction in lots of situations where others might get stressed out or start agonising is to think, Hey, it's no big deal, why make it out to be? And that's my way in my everyday life, too.

Q. Boris Becker has said that one of the assets that makes you such a great champion is your unique talent for keeping the world at arm's length, so that it doesn't affect your performance. Is that an accurate insight?

That's very accurate. Absolutely. I'm pretty good at separating my tennis from all the other stuff. I don't let a lot of people into my life. I don't even have a lot of acquaintances.

I'm driven. And that gets lost a little in the translation, because I appear to be so casual. But I know what I want, and I'll do anything I need to do to achieve it. Tennis-wise, that means I don't care about headlines. I don't care about how I'm seen. My priority is to win. I want to hold up that cup at the end. And over the years, I figured out what it takes to do that. It works for me, and that's all I know.

Q. Does that attitude - that distance you maintain - rub off in your personal life? Do those close to you find you hard to read?

I've heard that from a few different people, including Paul [Annacone, his coach]. He told me once that I was an enigma - that when I walk into the locker room, the other guys look at me like they can't figure me out. It certainly isn't something I do on purpose - like some image or aura I'm trying to create.

But it's different with my loved ones, my family. Nobody close to me has ever complained about me being remote. It does take a while for me to get to know someone, and at first I may not show what I'm thinking or feeling. But when I trust someone, I let the shield down. I open up.

Q. Did the extraordinary generation of players of which you were a part - Andre Agassi, Jim Courier, Michael Chang - play a part in your developing into a champion?

I wouldn't be where I am today if I didn't have those guys to push me. If you look at the chronology, you'll see that I was the last to peak. Michael won the French in 1989. I won the US Open in 1990, but then I disappeared while Jim went on a hot streak, winning the 1991 and 1992 French Opens and going to No. 1 in the world. Andre was right in the thick of it, too.

I wasn't jealous, but it did bother me a little to see them jump ahead. It made me wonder if I'd ever get to that point. That helped my motivation at a time when I was struggling with what I wanted out of the game. When I practised with Jim, it opened my eyes. There were moments when I thought, 'Yeah, I'm capable of beating this guy'. Why shouldn't I accomplish the same things?

Everyone seemed to set the bar higher for everyone else. We fed off that. We were all trying to make our marks, we were all insecure in some ways, and now I think we can all appreciate each other's accomplishments because we've been there ourselves. We know what it takes, and that creates a special bond among us.

Q. Does it amuse you that you're so often characterized as a laid-back guy, just surfing his talent to the top?

Yeah, a little bit. There's a competitiveness and an ability to focus that doesn't come across because it's well hidden, and that isn't what sports is about these days. I'm more of a Bjorn Borg, or a Stefan Edberg, than a John McEnroe. It probably has to do with how I was raised and my personality. I'm introspective, not a screamer.

I once played a round of golf with David Duval. As nice as he was to everyone else, I could see he wanted to play well. Before we played, he kind of went off by himself, to focus.

I noted that. I thought. Yeah, that's what I'm like, too.

Pete on His Parents

Q. Your parents, Sam and Georgia, are legendary for staying clear of the limelight. How would you describe them and how they influenced you?

I found tennis for myself. My parents just supported my interest in the game. It was a financial strain. For a while, my dad worked two jobs. [Sam Sampras, now retired, was both an engineer and a restaurant owner.] At first, he tried coaching me by reading books about the game. But that didn't last too long, and we joke about it now.

Dad turned my development over to my first coach, Pete Fischer. But he was right there, at a lot of my lessons, and driving me to matches and tournaments. So he was involved, but not on-court. He was smart enough to know what he didn't know.

My dad is a similar

kind of character to me. He keeps people at arm's length, but once he trust

and likes you, he'll be loyal to the end. That could take a while, though.

It took my younger sister Marion's husband, Phil Hodges, a year to break

through Dad's shield.

My dad is a similar

kind of character to me. He keeps people at arm's length, but once he trust

and likes you, he'll be loyal to the end. That could take a while, though.

It took my younger sister Marion's husband, Phil Hodges, a year to break

through Dad's shield.

He also doesn't come off as the warmest of people on the phone. When my childhood friends would call, they were always a little intimidated.

But Dad's also nervous. Neither he or my mum could bear to watch the 1990 US Open final on TV, so they wandered around a shopping mall near our house in California. They found out I had won when they passed by an electronics store and saw a TV tuned to a shot of me holding up the trophy.

When I was a junior, I played in higher divisions than my age. At 12, I'd be playing against 16 year olds. Often, right in the middle of some tough match, I'd look up at my dad. So what does he do? He waves goodbye and goes for a walk! And then I feel like I'm out there alone. I'm convince that those experiences shaped who I am today. They made me tough and independent. That's why you rarely see me looking at the players' box during a match.

My mum is the rock of the family. She used to feed me tennis balls because I was so crazy about the game, but she doesn't have many interests of her own beyond her kids.

She started out dirt-poor, moving to the States from Greece at the age of 25 without speaking a word of English, with a family that included six sisters and two brothers. Those first years, she sometimes slept on a cement floor. She became a beautician, and met my father when a friend of his encouraged him to check her out at the place where she cut hair.

Mum is the caretaker of the family. She has no education, but a lot of common sense, and she reads people well. Her talent is her heart, yet in her own quiet way, she's very strong.

Q. Your parents normally never come to watch you play, but this year they attended a Davis Cup tie and then, for the first time, Wimbledon. What prompted them to come and watch?

It's all part of a bigger picture that includes my moving back to Los Angeles.

I went off to live in Florida in my early twenties so I could focus on my tennis. The plan worked, but tennis began to consum me and I ended up enjoying the game less because of it. The time I spent with my family was mostly on the phone. Now that I'm back in Los Angeles, I fell I'm back where my roots are. I see my sister, Stella, three, four times a week. I drop by my parent's house once a week or so. It's been more good for my life to be back here. It's been great.

My dad sat through all the matches at the Davis Cup [against the Czech Republic] - a first. And when he came onto the court after I won the decisive rubber against Slava Dosedel and gave me a hug, it felt good. Really good.

I think they always wanted to be there with me, but they didn't want me worrying about them. And I would have - did they get their tickets okay? Is the hotel any good? That kind of stuff. The funny thing was that I actually had to make the point that I really wanted them there. I had to come out and tell them how much it meant to me for them to come.

Pete on Growing Up

Q. What are

your fondest childhood memories?

Q. What are

your fondest childhood memories?

No matter how long I think about it, it always come back to tennis. Playing

and winning. Getting out of school and going on court, grinding away. And

seeing improvements in my game.

I didn't have any friends in high school, except at the Jack Kramer Club where I practised. I didn't hang around with anybody, didn't play any other sports, didn't socialize. It got so bad that during lunch period I'd just go home. To the other kids I was just 'the tennis guy.' But I was okay with thay - I had a passion for the game.

I'm not the sentimental type. I didn't keep old teddy bears or my first tennis racket. In fact, I've got very little of my own memorabilia. It seems like every year I won Wimbledon, Ian Hamilton [a former executive at Nike, his clothing sponsor] would come into the locker room and ask for my shoes, autographed. I'd just laugh and give them to him.

Q. Do you feel you missed out on a normal adolescence?

Not really, although sometimes I think it would have been nice to go to college. I talk about that a lot with my sister Stella, who loved the independence, the parties, the fun. If I start to think I missed anything, I just have to remind myself that my job is to play sports. It's every kid's dream come true. I don't think it gets any better than this.

Pete on Religion and Marriage

Q. Do you believe in God? If so, how do you express your faith?

I absolutely believe. I used to go to Sunday school and Greek Orthodox Sunday services with my family. That's how my parents raised me and that's how I'll raise my kids some day.

Q. You showed a marked preference for dating actresses. Is there a hidden, flamboyant side to you?

I'm not real comfortable talking about this stuff. But if you're suggesting I live this racy bachelor lifestyle, that's not really accurate. I never went out to pick up girls. I never enjoyed it, and I'm much too protective about everything in my life to live loosely. I have gone to the occasionaly club, had a few drinks, a little fun, but I knew I'd never meet my wife at a nightclub.

Q. You have an extraordinary record at Wimbledon despite the fact that you didn't like grass early on and didn't get past the second round until 1992, the fourth year you played there. How did you turn it around?

For years, I felt that grass was unfair. My first few trips there, I thought, 'Ugh! This surface stinks'. I'm holding serve easily, but I'm going to lose, 7-6, 7-6, 7-6. My attitude was very negative, even though my coach Pete Fischer always insisted that I would do well there.

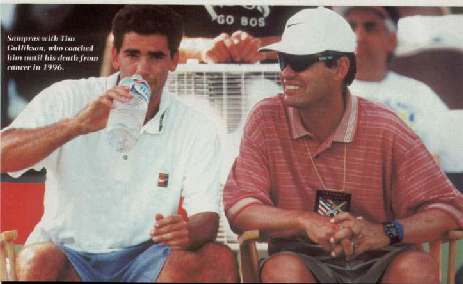

When Tim Gullikson took over as my coach, he felt the same way as Fischer. In 1992, we worked really hard on the two things you most need to win on grass: a good second serve and sharp service returns. That year, I was practising at Wimbledon one day on a court next to John McEnroe. He heard me making negative comments about the grass. He challenged me, saying I had a great game for grass but a crappy attitude. It was almost like a throwaway remark, but it must have sunk in, because here I am relating it eight years and seven titles later. I didn't get over the hump until I changed my negative attitude.

Pete on John McEnroe

Q. Is it fair to say that your relationship with McEnroe, currently your Davis Cup captain, has been volatile?

John and I are about as different as two people can get personality-wise, and that explains a lot.

We've had our share of miscommunication at times. John likes to stir things up. He thrives on controversy and emotional stuff in a way that I don't and, once you understand that, it's easier to deal with him. The big plus is that he's been there at that high level, and he knows how to handle players like Andre and me on court.

Q. In recent years, McEnroe has suggested you ought to be more colourful, show more emotion. Do you resent that?

To have someone tell me that I ought to act differently from how I am, or to make an effort to be exciting, is just the biggest load of garbage. We're all different.

It's baffling that anyone would presume to tell someone else to depart from their natural self. I have no apologies to make for the way I play or what I project.

I feel no shame in knowing kids are watching me play and maybe even taking their cues from it. And I think that my own quiet way has taken me to places I wouldn't have dreamed of ever reaching.

Pete on His Greatest Achievements

Q. What are some of your personal career highlights?

Right off, my

first US Open title. The 1999 Wimbledon final against Andre is right up

there too. It was my best-ever display of playing at a high level, against

a top-quality opponent, at a very big moment. I had it all that day. The

1995 Davis Cup final against Russia in Moscow is another one, because I

won three matches - two singles and the doubles - against a tough team on

clay, my least favorite surface. Two others stand out, but not because of

the the title matches: the 1997 Australian Open and the 1996 US Open.

Right off, my

first US Open title. The 1999 Wimbledon final against Andre is right up

there too. It was my best-ever display of playing at a high level, against

a top-quality opponent, at a very big moment. I had it all that day. The

1995 Davis Cup final against Russia in Moscow is another one, because I

won three matches - two singles and the doubles - against a tough team on

clay, my least favorite surface. Two others stand out, but not because of

the the title matches: the 1997 Australian Open and the 1996 US Open.

In Melbourne, I had a pretty easy final against Carlos Moya, but I almost lost to Dominik Hrbaty in five very tough sets in 140-degree heat in the fourth round. And at the '96 US Open I had that epic quarter-final match with Alex Corretja. [Sampras won a four hour marathon after throwing up on court during the fifth set tiebreaker; he went on to beat Chang in the final].

Pete on His Low Iron Condition

Q. It seems that the 'F' word in your career has been 'fitness'. Are your critics justified in claiming you aren't always in the best of shape?

After that Corretja match, Tom Tebbutt, a US newspaper reporter, wrote a story claiming I suffered from thalassemia, a low-iron blood condition that afflicts some people of Mediterranean descent. He was spot on. I have it. It sometimes makes me feel lethargic and a little out of it - that hang-dog look is partly because of the condition - especially in any very hot weather. I've been doing about all you can to offset it, which is taking iron pills. Other than trying to build up your iron level, there isn't much else you can do.

I've never admitted it until now because I didn't want my opponents to have that confidence of knowing I was playing with a deficit.

I've also had stomach problems, partly because of the way I internalize things and create stress. I had a small ulcer for about two years before that Corretja match without even knowing it. Playing matches in brutal heat didn't help either of those two conditions.

Apart from that, I don't have the personality to work as hard as, say a Jim Courier. Or the body. Leaner guys are different. I'm built more along the lines of a Stefan Edberg, who wasn't particularly known for his fitness, either. But the issue is always in my mind, and I've tried to do all I need both on the court and in the gym to maximize my game. My current goal is to keep my fitness level high during off weeks and breaks from the tour.

Q. That Corretja match is emblematic of how hard you work for your success at Flushing Meadows. Is it fair to say that the US Open has been a bit of a rollercoaster ride for you?

Well, I can't complain. I've won my own national title four times. But it has been an interesting ride and a less smooth one than I've had at Wimbledon.

Maybe it has to do with the US Open being the last Grand Slam event of a very long year. That may explain things like the herniated disc I had last year, just before the event started.

I always put myself through more torture than necessary at the US Open. I kind of raised the bar with my record from 1993-95 [Sampras won two Grand Slam titles in each of those years], and I remember in '96 people had these huge expectations. I hadn't won a Slam that year going into the Open, and I heard people whispering that I was slipping. I wanted that title. I wanted it so much, it turned my stomach upside down. That's how the Corretja thing came about.

Afterwards, I realized that tennis was consuming my life. I wanted so badly to win and I was so focused that I lost touch with reality. It took me wandering around the court, throwing up, to realise that. Later, I talked about it with Paul [Annacone]. He said I had to be careful, because I 'm too hard on myself. But that also helps explain why I've done so well.

Q. Do you feel like you've paid a huge price for your success?

Not at all. The recognition, having to live a life in the public eye, is probably the toughest part. But even that isn't too bad. It's flattering on one level, even though I do wish I could shut it off.

How can I complain about my lot? If I do, I probably should be slapped around rather than listened to.

Pete on Gripes with the Media

Q. Have you ever felt a desire for more sympathy than you've received?

On two occasions. One was that Davis Cup win over Russia. I'm really proud of that and feel it went unrecognized in the US. The other time was in 1998, when I set the record by finishing No. 1 for the sixth straight year.

I think that's a record unlikely to be broken, given the growin depth in the game. I wasn't calling any press conferences to complain that there wasn't a single American journalist in Europe covering that story. But when the European press kept asking me about it, I told them how I felt.

All right, it isn't going to excite the American media like somebody breaking the major league baseball single-season home-run record. And if people hear me complain about not getting enough credit, they're goiing to nail me. But I'm a human being. I have emotions. If I go through something that exacts such a heavy toll and feel it isn't recognized, it gets to me. I think it would get to anybody.

Q. What was the toll of that effort?

It was an awful period. I decided I really wanted the record, even if it meant staying in Europe and playing tennis for almost two months in a row, which is basically what I did. Unlike, say, winning Wimbledon, this record was a once-in-s-lifetime chance.

I don't confide in a lot of people, but after I lost to Richard Krajicek in Stuttgart at the end of October that year, I was still No. 2, with no guarantee of how things would turn out. At my next tournament, the Paris Indoors, I got Paul in my room and told him, "Hey, I'm really struggling with this. I can't stop thinking about this record issue. I'm putting so much into it. How am I going to deal with it if I don't get it?" It put me in a situation I don't experience a lot - the fear of losing. And that's a big thing.

But I coudn't make this obsession go away. Even when people ask me now if it was worth all the effort, the best I can say is "Yeah...sort of." Because the effort took so much out of me. My hair was falling out in clumps. I couldn't eat and I couldn't sleep. After seven straight weeks fighting to get the job done, I came home as mentally and physically tired as I've ever been in my life. And I ended up thinking, This isn't war. I'm not fighting for my life here.

People who know me understand that I torture myself sometimes just to win matches. I would almost say that in some ways, my life has been unbalanced. But I'm learning. Moving back to Los Angeles and spending more time with my family and girlfriend have helped me changed a little.

I realize it's okay to lose a tennis match. I'm not worried about that taking the edge off my competitiveness, because I really want to keep playing. If I slip up and never win a big title again, that's just the way it goes.

The one thing I won't do is get into another situation like that quest for the record.

Q. Has it been gratifying to see Andre Agassi re-emerge in the autumn of his career as a force in the game and a rival to you?

Undoubtedly. I've grown much more aware of what Andre has meant to my career during the last few years, since we've played each other a little more. Before, I didn't really see my relationship or rivalry with Andre as anything special. But now I do. I think we both realize now what's going on: We bring a lot to each other's table.

Our games match up great; whichever of us is playing better can really shine. And our rivalry is good for us and it's good for the game.

Ironically, it hurt my career in some ways not to have Andre around all the time. Navratilova had Evert. Borg had McEnroe, Becker had Edbert. I had Andre...at times. Our rivalry is as good as it will ever get for either of us. It helps us build our legacies. We both know that. We don't even have to talk about it.

Pete on How Tragedy Has Touched His Life

Q. You've shown great loyalty to your three coaches over the year: Fischer, Gullikson and Annacone. two of those coaches experience real tragedy. How did the fall of Pete Fischer [he was jailed in 1998 for child molesting] and Tim Gullikson's death from brain cancer in 1996 affect you?

I had long been separated from Pete's life by the time he went to jail. I didn't follow his case very closely, but I knew that no matter what he did, I couldn't abandon him as a friend. He was a big part of my life. He had a lot to do with what I am today, and you don't just desert someone like that. It's hard to see where he can ever go from here, when he gets out [of prison] in about a year. And that's sad.

Tim's situation really hit home, harder. He was with me when he got ill, and he died pretty much right before my eyes. I don't take what Pete's been through lightly, but I can't imagine anything worse than what Time had to endure.

It was hard playing through it all especially because I had to deal with it in a public way when it was such a deeply sad, privat experience. He certainly put the gift of life into a new perspective for me.

Q. What's the main thing you've learned about people throughout all these years?

That everyone isn't necessarily honest and that I'm only interested in people who are straight-shooters. My attitude is basically that I'm always going to be honest, and I expect people to be honest in return.

Q. How much of a future do you still have in tennis?

I can't put a number on that in terms of years, but I'll keep going as long as the desire last. The scary thing for me is that with the way I play and the way I feel, I believe that I'll have a chance to win Wimbledon, or the US Open, even at 35.

I see myself being around for a while. Yevgeny [Kafelnikov] is convinced

that I'm the main obstacle in his path to winning Grand Slams and being

No. 1 for an extended period. Whenever I see him in a locker room, he asks

me, "So Pete, how much longer are you going to play?" My stock

answer is, "Gee, I don't know; how much longer do you think you'll

play?"

Special thanks to Samprasfanz member Georgia Christoforou for sharing this interview.

Back to Archives - 2000 | News